Beat the COVID-19 blues! Keep your book club active.

Reading Between the Wines...

These ladies know how to make someone feel welcome!

Last Thursday, my wife and I attended the “Reading Between the Wines” book club in Austin to discuss my novel, Death in Panama. They prepared a fantastic dinner, including empanadas and patacones! But the best treat of the evening was hearing the enthusiasm they had for my book.

They asked a lot of insightful questions, indicating their experience in reading the book was what I’d hoped for. I wanted to tell an entertaining and interesting story and yet provide readers with more; namely, complex, realistic characters dealing with personal problems and ethical dilemmas that challenge readers to consider how they would deal with similar situations.

Thank you, ladies.You got it.You made my day!

Are we being too sensitive?

Barely a day goes by that someone is not in the news, apologizing about something or being told they should.

The latest example is Ilhan Omar, a Congresswoman from Minnesota, who has been accused of making anti-Semitic remarks. Before that, it was sixteen-year-old Nick Sandmann, who was part of a group of Catholic high-school students waiting on their bus in front of the Lincoln Memorial. When a video of Nick surfaced, showing him wearing a MAGA hat and smiling at a Native American activist who approached the group of boys, he was lambasted by social media, as well as mainstream outlets such as the Washington Post and CNN. They accused him of being a racist and the product of “white privilege,” among other things. Nevertheless, a quick look at the entire video shows Nick did nothing wrong. The media grossly overreacted.

But my purpose here is not to debate whether Ms. Omar’s comments were inappropriate or merely an expression of her views on U.S. policy toward Israel. Nor am I going to comment on whether Mr. Sandmann will—or should—be successful in his lawsuits against the Washington Post and CNN. My purpose here is, in part, to point out that such events seem to dominate public discourse much more than important issues, such as our country’s relationships with China and North Korea, for example.

Why is it that so many people seem to be fixated on who owes whom an apology?

The political commentator George F. Will described it this way:

“The cultivation - even celebration - of victimhood by intellectuals, tort lawyers, politicians and the media is both cause and effect of today’s culture of complaint.”

It wasn’t always this way. There was a time, not too long ago, when folks didn’t take themselves so seriously. Now, it seems, you can find yourself offending someone without even realizing it.

The comedian, Jerry Seinfeld, has stopped performing at college campuses because they are “too politically correct.” As he explained, “College students throw around ‘that's racist / sexist / prejudice’ without knowing what they're talking about.”

Even Dr. Seuss has come under fire. Researchers Katie Ishizuka and Ramón Stephens recently published the results of their study of his iconic children’s books in an article titled: “The Cat is Out of the Bag: Orientalism, Anti-Blackness, and White Supremacy in Dr. Seuss's Children's Books.” The title says it all.

Where does all of this end?

There’s no doubt that our society has become hyper-sensitive. Clearly, many folks need to take a deep breath and “lighten up.” But pendulums have a way of swinging to the extremes. Some of the ridiculous claims of victimhood and calls for apologies could cause a backlash, which wouldn’t be good for our society either. If we start dismissing calls for apologies—even reasonable ones—as simply more chatter from the “snowflake generation,” then we run the risk of not apologizing in instances when we should.

So that begs the question: When should we apologize?

The simple answer is that one should apologize when he or she has wronged someone else. Sometimes, it is obvious when that happens. Many times, it’s not.

Deciding whether one has wronged someone else requires careful thought about whether it is reasonable to conclude that something one has said or done is offensive. But as any lawyer will tell you, what is “reasonable” depends on innumerable factors. So, perhaps the answer is not so simple.

No doubt, questions of right and wrong can be clear. No one would argue that murder is acceptable, for example. But there are grey areas, and they seem to be expanding rapidly. Should I apologize for being insensitive to another’s political beliefs if I disagree with them? What about religion? Although most people refrain from making derogatory remarks about another’s religion, we’ve all heard jokes involving the Pope or Baptists or Jews or fill-in-the blank.

To some extent the answer lies in considering how much another person might identify with something; that is, how much it is a part of who they are. If it is something immutable, such as the color of a person’s skin, then making that characteristic the butt of a joke is clearly insensitive.

But what if someone takes himself too seriously? Is it really reasonable to conclude Dr. Seuss was a racist, sexist, xenophobe? Or that the Washington Redskins should change their name because it’s offensive? Is an apology called for when someone is offended because he takes himself too seriously? Probably not. But who decides if someone is taking himself too seriously?

Politics are another matter, in my humble opinion. Having strongly held beliefs should simply mean you’re ready to defend them. Political beliefs do not define an individual, as evidenced by the transformation of some public figures such as Ronald Reagan and Thomas Sowell, each of whom started his adult life as liberal and later became an ardent conservative. To me, one’s politics are fair game for criticism, and if someone doesn’t like it, then . . . well . . . he can lump it. That said, I also believe that a political argument should never destroy, or even undermine, one’s relationship with a family member or friend. And, the discourse should be respectful, not ad hominem.

So I guess I can’t offer clear guidance about when one should apologize, other than to say we should each examine our own heart. I was prompted to write this blog post, because I recently had an occasion to do just that.

As the readers of my novel Death in Panama know, it is loosely based on my experiences while stationed in Panama where I prosecuted a murder case. The novel also makes observations on Army life and briefly on Panamanian society and life in the Canal Zone.

To my dismay, I received an email from a reader who grew up in the Canal Zone and felt that my portrayal of Zonians was insulting. It would have been easy for me to dismiss her complaint, especially since much of the book, including some of the stories about Zonians, is based on my actual experiences in Panama. But I didn’t do that. Instead, I tried to understand why she might have been offended and concluded that her complaints were justified. So, I apologized. Later, I began to wonder whether other readers might be similarly offended, in particular because last summer I sold a number of copies of my book at the Panama Canal Society Reunion. So, I decided to publish an open letter to the Society in an effort to explain myself.

I’m not suggesting I’m any sort of “good guy” for apologizing. On the contrary, the author of the email was correct: I should have been more sensitive, especially with regard to something so personal as someone’s identity; that is, being a “Zonian.”

Questions of right and wrong are as old as time. I’ve concluded that there are no easy answers for many of them. All that well-intentioned people can do is try to be sensitive and respectful of others; refrain from taking themselves too seriously; and most important, as the Good Book says: “be quick to listen, slow to speak and slow to become angry.”

A Tale of Two Visits to Panama

Pope Francis’s recent visit to Panama caused me to reflect on the visit of another pope at another time. On March 5, 1983, while I was still stationed in Panama and struggling through the events that led me to write Death in Panama, Pope John Paul II arrived in Panama to an enthusiastic crowd numbering in the tens of thousands. Several of us staged a pope-watching party on the roof of my neighbor’s quarters, hoping to catch a glimpse of the charismatic pontiff as he delivered his major address to the people of Panama.

What I remember most about that visit was that Pope John Paul II admonished the masses gathered on the tarmac of Albrook Air Force Station to reject the temptation to violence, which was then roiling Central America.

“There are those who wish you to abandon your work and take up the arms of hate to struggle against your brothers. You should not follow them. Where does this path of violence lead? Without a doubt, it increases hatred and the distance between social groups. These methods, completely contrary to the love of God and the teachings of your Church and of Jesus Christ, mock the reality of your noble aspirations and provoke new evils of social and moral decay.”

The pontiff had recently come from Nicaragua where he had scolded Father Ernesto Cardenal, who was then serving in the Sandinista government as the Culture Minister, telling him to “straighten out your position with the church.”

Pope John Paul II was concerned about a growing trend in Latin America in general, and Nicaragua in particular, where Marxist revolutionaries had allied themselves with Catholics in support of what had come to be known as “liberation theology,” originally advanced by Father Gustavo Guitiérrez, a Peruvian priest. Liberation theology is a melding of Christian theology and Marxist socio-economic analyses that focuses on concern for the poor and advocates political liberation of oppressed peoples as the solution. Pope John Paul II clearly wanted to sever those ties, which he believed were a threat to the established order of the church.

How different the recent trip of Pope Francis to Panama. Far from avoiding political entanglements, the pontiff waded into them, telling a crowd at a seaside park in Panama City, “This is the criteria to divide people: The builders of bridges and the builders of walls; those builders of walls sow fear and look to divide people.” The remark was clearly aimed at President Trump’s proposal to build a wall on the U.S. border with Mexico. And it wasn’t the first time the pope criticized a fundamental pledge of the Trump campaign. In 2016 he said, “A person who thinks only about building walls, wherever they may be, and not building bridges, is not Christian. This is not the gospel.” For his part, the ever-pugnacious, then candidate Trump fired back, calling the pontiff’s comments “disgraceful” and saying “No leader, especially a religious leader, should have the right to question another man’s religion or faith.”

The contrast between the two popes is obvious, although I suspect one’s view on the propriety of their respective behavior depends, in large part, on one’s political views.

In the early 1980s the Catholic Church, under the leadership of Pope John Paul II, provided millions of dollars of financial support to Solidarity, the Polish labor union that was the catalyst for nationalist movements across Eastern Europe that fatally weakened the power of the central Soviet state. Those who despise communism applaud the role the pontiff played in the demise of the evil empire, even though he involved the Catholic Church in what was clearly a political struggle, contradicting the advice he had delivered in Panama.

In 2019, those who believe that the poor remain poor because they are oppressed by the societies in which they live support Pope Francis’s embrace of a progressive theology that emphasizes the church’s concern for the poor. Recently, he went so far as to wish Father Guitiérrez, the father of liberation theology, a happy 90th birthday, writing “Thank you for your efforts and for your way of challenging everyone’s conscience, so that no one remains indifferent to the tragedy of poverty and exclusion.”

The world turned over many times between those two visits. The Challenger exploded. The Iron Curtain fell, and the Soviet Union disintegrated. There have been wars and more wars. Computers have connected us like never before, and yet feelings of isolation have reached epidemic proportions, leading to record levels of suicide. Women have assumed roles in society that their mothers could never have imagined. The percentage of babies born to unmarried women has soared. And, the poor are still with us. What does all this mean to the Catholic Church?

No doubt, being the leader of the largest and oldest Christian denomination has its challenges. There will always be those who attempt to misrepresent what the pope says and does for their own purposes. And, the church has its own problems, involving what some consider to be archaic doctrines on sexuality, as well as recurrent instances of failing to properly address sexual abuse cases involving the clergy. But despite all of its troubles, few institutions throughout history have done as much good as has the Catholic Church. Currently, it is the largest non-governmental provider of education and medical services in the world.

As a member of the United Methodist Church, I don’t follow the current events of the Catholic Church or the pontiff. Nevertheless, I wish both the institution and its leader well. Prompted to consider these two popes, because of their visits to Panama, I’m reminded of the importance of grounding one’s beliefs in basic principles. For example, as I explained in another blog post, I’m an American because I believe in the fundamental importance and power of freedom, even though I might disagree with another American’s view of the limits that should be placed on it. As a Christian, I try follow the Great Commandment: to love God with all my heart, soul, mind, and strength, and to love my neighbor as myself. So, if I disagree with what a pope might say or do, I hope I’m able to distinguish whether something is fundamentally wrong or whether I’m really just disagreeing with one man’s view of how to follow the Great Commandment.

What Does it Mean to be an American?

We—we “Americans”—seem to be more divided today than at any time I can remember. The Left can’t stand the Right, and the Right thinks the Left is comprised of “snowflakes.” Progressives think “the rich don’t pay their fair share,” while those in the top one percent of income earners lament that they contribute almost 25% of all federal revenues collected. And, there are those among us who seem to look for opportunities to divide us along racial lines in ways that I suspect the students in my integrated high school would have found laughable. Back then, we all made an effort to get along, although perhaps not always as well as we should have.

What prompted me to write this essay was a report I saw about a television personality who was downright gleeful when she learned that President Trump’s proposed summit with Kim Jong-un, the leader of North Korea, might not take place. Gleeful. It made me sick. Why would any American, regardless of her political beliefs, be happy about something like that? Aren’t we all in this together? Don’t we all want what’s good for America?

But those questions caused me to ask another—more profound—question: What exactly does it mean to be an American?

We are certainly not a pedigreed nation. We are descendent from a variety of races, religions, and cultures, and yet we have come together as Americans. So, what is it that binds us together? What makes us Americans?

I think the answer is simple: Americans believe in freedom. It is our core value, enshrined in the Declaration of Independence, and more important than any other. It defines us. Americans believe that freedom is a God-given right—or, if you prefer, a fundamental part of the natural order. Freedom is not granted to Americans by our government. On the contrary, we came together to form a government precisely because we wanted to protect our freedom. The government answers to us.

But that begs another question: What exactly does it mean to say we believe in freedom?

A simplistic view would say that freedom means you get to do what you want. But then, what about the other guy’s freedom? What if your exercise of your freedom affects his exercise of his freedom?

We came together to form a country that respects individual freedom, but there are necessary limits to that freedom. For me, the limits fall into two categories. First, my exercise of my freedom should not impede your exercise of your freedom. I might want to be free to target practice with a rifle in my backyard, but that would inhibit my next-door neighbor’s ability to be free to sunbathe in his backyard. Second, my exercise of my freedom might be limited for the common good. For example, the doctrine of eminent domain—the power of the government to take private property for public use—is recognized in the Fifth Amendment to the Constitution, which says the government can take private property for public use, provided the owner receives just compensation. In other words, I shouldn’t be able to hold up the construction of a desperately needed highway because I don’t want to sell my land or grant an easement to come across it.

It’s my belief that the divisiveness we are facing today is borne of dramatically different views about the extent of those two categories of limitations on our freedom.

Back in the 1960s, the courts ruled that a restaurant owner is not “free” to refuse service to a customer based on the customer’s race. It’s regrettable that they had to base those rulings on the government’s power to regulate interstate commerce. For some reason that seems to diminish the morality of the decisions. But they got the job done. They promoted freedom in our society at large.

But where does it end?

Today, am I free to eat a ham sandwich on an airplane, even if it offends the vegan sitting next to me? The government hasn’t gone that far yet, although there are some who think it should. Is that correct? Should the government require a baker to make a wedding cake for a gay couple, even if it offends the baker’s sincerely held religious beliefs? What is the limit of the government’s ability to restrict an American from exercising his or her freedom to do something because it offends someone else? I cannot say precisely, but I think we must be very careful in drawing those lines.

Certainly, no one’s exercise of freedom should endanger someone else physically. And religious beliefs should be respected, although there are limits to that. Most Americans would agree that Muslim teachers should not be allowed to attempt to indoctrinate Christian students. But then, Baptist teachers shouldn’t be allowed to proselytize to agnostic students either, should they? We should not protect certain behaviors simply because we agree with them. Restrictions on our freedom should be fair to all. We most assuredly are not a theocracy, but I also don’t want the government to trample on my freedom to exercise my religious beliefs.

And how should the government address things that offend people but have nothing to do with religion? If we enter the realm of having the government worry about someone else’s psychological endangerment, I think we’re entering troubled waters. But then, we have laws against child pornography, don’t we? In short, there aren’t any easy answers.

What about that other category of limitations on our freedom: limitations for the common good?

The classic example of that kind of limitation involves taxes. The government takes part of what we earn to spend for the common good, such as expenditures for the military and law enforcement. People who support Senator Bernie Sanders believe the government doesn’t take enough of what we earn, while those who support Senator Rand Paul believe the government takes far too much. Thus, there are disagreements about both how much a person’s freedom should be limited for the common good and what constitutes the common good.

And those disagreements—like those arising from the other category of limitations on our freedom—should be debated. But that’s not what’s happening.

Today, it seems that every discussion on limiting the freedom of Americans is cast in absolute terms of right and wrong, allowing no room for disagreement, no room for compromise. In fact, there is no real debate. The discussion—if you can call it that—goes something like this: If you disagree with me, you are immoral, you are a fascist, you want to kill children or old people or destroy the environment. Or, alternatively, you are immoral, you are a fascist, you want to take away my hard-earned money and waste it, you want to censor what I say on a college campus or tell me what to do with my own property or take it away and give it to someone else because you claim it’s for the public good. That kind of discourse is toxic to our American society.

It is my sincere hope that we, as Americans, get back to the core principle that defines us. Freedom. We must recognize that there are limits to our freedom, but we must demand that all leaders in our society—political, civic, and business—engage in a civil debate about those limits and stop demonizing those with whom they disagree. And we should be suspicious of their motives. Are they espousing something based on sincerely held beliefs or because it helps them obtain or maintain some kind of power? If we don’t require our leaders to be respectful and sincere, then I fear this wonderful experiment in self-government that has lasted over 200 years will come to an end, and we will become but a brief episode in the expanse of human history, most of which is characterized by either tyranny or anarchy.

The Human Side of Three Warriors

My daughter gave me a copy of The Generals by Winston Groom. It’s a special book for several reasons.

First, she got my copy autographed by the author. Mr. Groom lives in Point Clear, Alabama, adjacent to Fairhope, Alabama, where my daughter lives. Some say Fairhope was the model for Greenbow, Alabama, the fictional home of Forrest Gump—which leads me to my second reason.

Winston Groom is also the author of the novel Forrest Gump, which we all know was made into an Academy Award-winning movie starring Tom Hanks. Although the script writers took some liberties with Mr. Groom’s book, the story remains a work of art—something that can be enjoyed from many different perspectives. It’s one of my favorites.

Finally, The Generals—to get back to the book at hand—concerns three titans of World War II: George Patton, Douglas MacArthur, and George Marshall. I’ve been a student of military history all of my life, which in part explains my choice of colleges. But Mr. Groom’s book revealed a number of things about the personal lives of these three men that I didn’t know, despite having read a number of books about each of them. To be sure, there is much to learn in The Generals about their military exploits and incredible achievements, but what I found fascinating, though somewhat gossipy, was his discussion of the men behind the uniforms.

General Patton was, of course, the swashbuckling tank commander, with whom I first became enamored when my dad and I saw the movie Patton. During WWII, my dad was part of the 12th Armored Division, which was detailed to General Patton’s famous Third Army for a time. Mr. Groom’s extremely well-written book revealed some personal things about General Patton that went beyond his entanglements with the press, his colorful statements, and the infamous episode when he slapped a young soldier suffering from battle fatigue.

Shortly before graduating from West Point, Patton asked Beatrice Ayer, the daughter of a wealthy Massachusetts businessman, to marry him. In an example of the flamboyant style for which he became known, Patton asked Beatrice’s father for her hand on a Sunday morning in January 1909. He rode up the twenty-six stone steps of the Ayer mansion, riding a large white horse. Still mounted, he approached young Beatrice, who was seated on the terrace, and made the horse bow in front of her. His father-in-law-to-be later wrote to Patton, saying: “All right. You let me worry about making the money, and you worry about getting the glory.” Patton took that instruction to heart.

A few years after graduating from West Point, Patton was assigned to General Pershing, who was busy pursuing Pancho Villa along the Mexican border. At a Christmas dance at Fort Bliss in 1915, Pershing, who had recently lost his wife and children in a fire, met Patton’s twenty-nine-year-old sister, Nita, and took a fancy to the tall blonde. Despite a twenty-seven-year age difference, the two became lovers, and Pershing later asked Nita’s father for her hand in marriage. But then World War I intervened, delaying their engagement. Following the war, the now much-celebrated Pershing ended the relationship. Nonetheless, Patton’s career during WWI certainly wasn’t hurt by the fact that General of Armies John Pershing, the senior U.S. Army commander, had been—and perhaps still was—smitten with his sister.

Mr. Groom tells us that Patton also wrote poetry, composing some of it while in combat. Although he was certainly no Yeats, some of his verse is pretty good, albeit reflective of his warrior ethos:

So let us do real fighting, boring in and gouging, biting,

Let’s take a chance now that we have the ball.

Let’s forget those fine firm bases in the dreary, shell raked spaces,

Let’s shoot the works and win! Yes win it all!

Like General Pershing, Patton took his own detour from the “straight and narrow,” although in his case he was still married. While in his fifties, Patton had an affair with twenty-one-year-old Jean Gordon, the daughter of his wife’s half sister. Years later, Jean showed up again as a Red Cross worker in Paris when Patton was busy fighting battles and conquering territory in western France. He was alerted to her presence by a letter from his wife Beatrice, to which he tersely replied: “We are in the middle of a battle, so I don’t see people. So don’t worry.”

General MacArthur was no less ensnared by affairs of the heart. Surprisingly, one such affair also involved the aging General Pershing. While assigned as Superintendent of West Point in the early 1920s, MacArthur attended a fashionable party in Tuxedo Park, located south of West Point and north of New York City, where he met a Baltimore socialite and multi-millionaire heiress named Louise Cromwell Brooks. She was a divorcee with two children, though more significant than that, she had also caught the attention of General Pershing, who had been seen with her at social affairs in Washington. Nevertheless, she and MacArthur were soon married—much to the chagrin of both MacArthur’s mother, Pinky, who still doted on her son, and, of course, General Pershing, the highest ranking officer in the Army at the time. Not surprisingly, MacArthur soon found himself relieved of duty at West Point a year early and on his way to the Philippines. His marriage to Louise didn’t last; she divorced him in 1929.

At the age of fifty, MacArthur was made Chief of Staff of the Army and moved into Quarters Number 1 at Fort Myer, Virginia, with his possessive mother. Always rather eccentric about his military attire, he began wearing a Japanese kimono in his office and paced around fanning himself with an Oriental fan. And, unbeknownst to his mother, he took a mistress—a Eurasian woman in her twenties named Isabel Cooper. When the Washington Post and columnist Drew Pearson threatened to expose that relationship, MacArthur had to drop a libel suit he had filed against them as a result of their reporting on his treatment of the bonus marchers, a group of WWI veterans who had gathered in Washington, D.C. in the summer of 1932 to demand immediate payment of their service certificates. Apparently, it wasn’t scandal that MacArthur feared: he didn’t want his mother to find out he had a mistress!

In 1935, MacArthur became Military Advisor to the Commonwealth Government of the Philippines and a field marshal in the Philippine Army. On his voyage to the Philippines, he met thirty-seven-year-old Jean Faircloth, the granddaughter of a captain in the Confederate Army who had fought against MacArthur’s father at the Battle of Missionary Ridge in the Civil War. They were later married and produced a son, Arthur MacArthur, who is still living, though under an assumed name. By all reports, MacArthur was a devoted father, despite his somewhat advanced age and, of course, his responsibilities during WWII. During his limited spare time, he read to young Arthur from Grimms’ Fairy Tales and other children’s books and trained him in close order drill.

General George C. Marshall, known for his superb organizational and planning abilities, especially during WWII, was much less of a ladies man than either Patton or MacArthur. During his senior year at the Virginia Military Institute, he was named First Captain (the senior cadet) and fell in love with Elizabeth Carter Coles, who lived in the shadow of the entrance to VMI. The day after passing the Army’s entrance exam in 1902, he married her and unfailingly cared for her until she succumbed to the heart ailment that had plagued her all of her life. Following her death he wrote to General Pershing: “Twenty-six years of intimate companionship, since I was a mere boy, leave me lost in my best effort to adjust myself to future prospects in life . . . However, I will find a way.” Luckily he soon found a cure for his broken heart. In 1928, while attending a dinner party in Columbus, Georgia (near his station at Fort Benning), he met Katherine Tupper Brown of Baltimore, a recent widow with three children. The two were married in 1930 and remained so, without scandal or affairs, until the general’s death in 1959.

Besides these glimpses into the private lives of three larger-than-life heroes, Mr. Groom explains the remarkable achievements of these men in their service to our country. But I must say that the personal anecdotes were something I hadn’t encountered before, and I thoroughly enjoyed them. It showed the human side of these great captains. Spend some time with The Generals. It’s well worth it.

A Timely Old Lesson

Last Thursday night, my wife and I attended a performance of Les Misérables at the Music Hall at Fair Park in Dallas.

I was blown away.

I’ve seen the musical on Broadway and in Houston, but I’ve never seen a production like this one. The performers were fantastic, the orchestra was exquisite, and the large venue was packed.

As I sat there enjoying the beauty of Claude-Michel Schönberg’s masterful score, I was struck again by the profound message of Victor Hugo’s original story: love and mercy are transformational. It is a message as old as the Gospel.

The first example comes when the benevolent Bishop Myriel gives Jean Valjean food and shelter, a kindness which Valjean returns by stealing some silverware. When the police later capture Valjean, the bishop pretends that he gave Valjean the silverware and offers him two silver candlesticks, which he “forgot” to take. That explanation spares Valjean from life imprisonment as a repeat offender. Bishop Myriel then tells Valjean that his life has been spared for God and that he should use the money from the silver candlesticks to make a new life for himself. And that he does, becoming a successful businessman and mayor of a town, although in the process also breaking the terms of his parole, which could send him to prison for life.

Years later, Valjean (now living under the pseudonym Madeleine) intervenes when his old nemesis, Inspector Javert, arrests a young woman named Fantine for striking a dandy who has harassed her in the street. Although he risks being discovered by Javert, Valjean orders Javert to take Fantine to the hospital and later promises her that he will bring her daughter Cosette to her.

Valjean again shows compassion when he learns that an innocent man will be tried as the Valjean who broke his parole. He goes to court and reveals his identity, knowing that it could mean his arrest and imprisonment for life. He returns to the hospital and promises Fantine that he will find Cosette and care for her. Javert arrives to take Valjean into custody, but he overpowers the inspector and escapes.

The plot unfolds as Valjean rescues Cosette from her unscrupulous caretakers, takes her to Paris, and gives her a new life. She grows up and meets and falls in love with a young revolutionary named Marius. After the revolutionaries take to the streets, Javert infiltrates a group that has erected one of the barricades around the city. When Javert is recognized by one of the revolutionaries and doomed to be executed, Valjean asks to be the one to execute him. But as soon as they are alone, Valjean releases him. Javert tells Valjean that he will never stop pursuing him and that he has made no bargain with him. Valjean responds that he is releasing him unconditionally.

Valjean returns to the barricades and rescues the seriously wounded Marius by carrying him to safety through the Paris sewers. But when he emerges from the sewer, he finds Javert waiting for him. Valjean begs Javert to allow him to take Marius to a doctor, and Javert reluctantly agrees. Javert can’t reconcile Valjean’s selfless behavior with Javert’s belief that he is an inveterate criminal. Unable to compromise his principles but no longer able to hold them sacred, Javert commits suicide by jumping into the Seine.

I don’t know whether Victor Hugo intended for Valjean to be a Christ figure, but he certainly describes a man who was transformed by love and mercy to become a noble and generous soul. And then there’s Javert, who seems to be a hopeless Pharisee, living a life that brings joy to no one, including himself.

In the current age there is far too much acrimony and hate—far too many Javerts—and not nearly enough love and mercy. I hope that those who watched the marvelous performance of Les Misérables will reflect on the transformational power of love and mercy in our troubled world and put the lesson into practice.

The Value of Patient Discernment

No one I know—with the possible exception of my niece—is a bigger fan of Harper Lee’s classic, To Kill a Mockingbird, than I am. So it was with no small amount of trepidation that I approached her second novel, Go Set a Watchman, the publication of which has been met with considerable suspicion. Some commentators have claimed that Ms. Lee’s declining health and the death of her older sister, who was an attorney and the gatekeeper for, and protector of, Ms. Lee for most of her life, suggest that her decision to publish the second novel was not completely knowing and voluntary—a view that is also supported by Ms. Lee’s repeated assertions since the publication of To Kill a Mockingbird that she would never write or publish another novel.

But all of that is part of the backdrop. What’s more interesting is the book.

Go Set a Watchman gets off to an incredibly slow and listless start. Twenty-six year old Jean Louise Finch (a/k/a Scout) returns to Maycomb, Alabama, from New York to visit her ailing father Atticus. The year is 1957, notably after the landmark Supreme Court case of Brown v. Board of Education. Brother Jem Finch has previously died of the same congenital heart defect that claimed their mother. There are three characters not found in To Kill a Mockingbird. Uncle Jack, Atticus’s brother, is a retired doctor and aficionado of eighteenth and nineteenth century literature. He also functions as a sort of mentor for Scout. Aunt Alexandria has taken Calpurnia's place following the housekeeper's retirement and is caring for Atticus, who still attends to his law practice. Aunt Alexandria is a foil against which Ms. Lee smashes the shibboleths of Southern womanhood. Let’s just say she’s no “steel magnolia.” Finally, there’s a grown-up childhood sweetheart named Henry (“Hank”) Clinton, who is a World War II veteran, now lawyer working for Atticus. There is much discussion about whether he and Scout will get married.

The novel begins with numerous long and tedious descriptions of mundane events and flashbacks to Scout’s childhood. The writing is so bad it’s hard to imagine that the great Harper Lee is the author. Where the book gets interesting is when Scout discovers a pamphlet entitled “The Black Plague” among Atticus’s papers. Later, Scout follows Atticus to a “Citizens’ Council” meeting at which Hank is also present. Atticus introduces a speaker who delivers a speech full of racist invective. For fans of To Kill a Mockingbird, who see Atticus Finch as an American Cincinnatus, this comes as a shock. A reviewer in the New York Times is typical of many when she writes that readers will share Scout’s horror at learning that Atticus “has been affiliating with raving anti-integration, anti-black crazies . . .” Such reviews typically make liberal use of the words “bigot” and “racist.”

What unfolds following the revelation of Atticus’s affiliation with the Citizens’ Council is what makes the book worth reading. Ms. Lee provides a thoughtful and careful discussion of race relations at the beginning of the modern civil rights movement and addresses many difficult questions that she avoided in To Kill a Mockingbird. She paints the picture carefully with small strokes and delicate shades. Unfortunately, reviewers like the author of the New York Times review see only the bold strokes in primary colors. I suspect their failure to appreciate the subtlety of Ms. Lee’s work springs from their desire to claim a position on the moral high ground, rather than to try to understand the complex nature of the dramatic social changes that were taking place at that time. It’s easier to lump people into predetermined categories than it is to truly understand what they think and feel.

Scout struggles with the same issues. She is highly critical of her father’s involvement with the Citizens’ Council and claims she won’t marry Hank because of his involvement. Nevertheless, after listening to Uncle Jack’s somewhat tortuous explanation of Atticus’s actions, she begins to understand that her father is an intelligent man of honor—a complex human being, not a super hero. (One of the lessons of my novel, Death in Panama, is that much harm can result when people are too quick to draw conclusions that are either unsupported by the facts or based on a lack of understanding. The risk of such harm is especially acute when the conclusion concerns something important, such as whether someone is a racist. The care one takes in drawing a conclusion should be directly proportional to the importance of the conclusion.)

If the reader can get past the tedious parts of Go Set a Watchman, there is much to learn, although it requires setting aside simplistic, preconceived notions of how the civil rights movement began and listening for the soft subtle voice of Ms. Lee.

Too Much in One Book?

A friend recommended that I read the Pulitzer Prize-winning novel Middlesex by Jeffrey Eugenides. Published in 2002, the book tells a long—and mostly satisfying—story about a protagonist who is intersex; that is, someone born with one or more variations in sex characteristics so that the person does not fit the typical definitions for male or female bodies.

What I found confusing about Middlesex is that the novel is really two stories in one, and I felt that each story suffered from having to elaborate on the other.

On the one hand, Middlesex is the story of a family of Greek immigrants. It begins in 1922 when Eleutherios (“Lefty”) and his sister Desdemona flee Smyrna, Greece (now Izmir, Turkey), during the chaos of the Greco-Turkish War, and board a passenger ship bound for the United States. Although they are brother and sister, they decide to get married by the ship’s captain. Having come from a small village where marriages between cousins are commonplace, they justify the relationship, even though they know it’s wrong. That union plants the seed, as it were, for the other story. More about that later. The family saga continues as Lefty and Desdemona make a life for themselves in Detroit, Michigan. The family lives out the American dream of financial success, despite setbacks caused by the decay of Detroit, which Mr. Eugenides poignantly describes.

Then there’s the other story in Middlesex. The grandchild of Lefty and Desdemona begins life as a little girl named Calliope (“Callie”), but as she reaches puberty she discovers that she’s more male than female. After she’s injured by a tractor, the doctor treating her discovers that she is intersex. That fact was not previously discovered because Callie’s family doctor is an aging Greek physician who had helped her grandparents escape to the United States. After the secret of Callie’s condition is out—so to speak—her parents take her to a clinic in New York, where she undergoes numerous tests and examinations by the world’s leading expert on intersex. When Callie learns that she’s going to have sex reassignment surgery, she runs away and assumes a male identity.

Hitchhiking cross-country, she begins calling herself “Cal.” She encounters a number of strange characters and eventually reaches San Francisco, where she (now he) works in a strip club as “Hermaphroditus.” When the club is raided by police, Cal is arrested. Later, he’s released to the custody of his brother, who has come to California to retrieve him. Cal’s brother tells him that their father has died, and the siblings return to their family home on Middlesex for the funeral. When Cal goes to see his grandmother, Desdemona at first thinks he’s Lefty, but recalling stories from her old village about children born of incest, she soon realizes that Callie is now Cal. Desdemona reveals to Cal that her husband, Lefty, was also her brother, and the story obtains closure. The consequence of Desdemona’s sin is now laid bare.

Obviously, based on the awards and acclaim it has received, Middlesex is deemed to be a great work of literature. But, as I read it, I kept thinking about Curly (Jack Palance) in the movie City Slickers, who told Mitch (Billy Crystal) that the secret to life is “one thing.” Middlesex is a wonderful book, but it is most assuredly not one thing. It is a family saga, a coming-of-age story, a social commentary on decaying cities, and. . . a detailed discussion of the challenges of living as an intersex. It’s a good book, but I think Mr. Eugenides tried to accomplish too much in one book. Still, it’s worth a read. Hey, it won the Pulitzer Prize.

Renaissance Man

My wife and I have begun a book tour out West. Our first stop was in El Paso, Texas, where we stayed with my West Point classmate, Dr. Stephen P. Hetz, MD, Colonel, US Army (Retired), and his wife Mary.

One of the greatest blessings I’ve received in my life is being a member of the West Point Class of 1975. I entered the class on a stormy July 1, 1971, with no brothers of my own and graduated on a sunny day four years later with 862. They are my closest friends and have been with me through thick and thin.

Steve is a special friend. We went to through all the challenges West Point had to offer, but also got to go helicopter school after our second academic year, known as Yearling Year. We went to Fort Wolters, Texas, for instruction and logged over forty hours on the Army’s TH55 training helicopters, known affectionately as "Mattel Messerschmitts."

Years after graduation I encountered Steve again at Fort Gordon, Georgia. By then he was an Army surgeon, and my wife was in need of an appendectomy. Because of our relationship, Steve didn’t perform the surgery, but he ensured that everything went smoothly and was there for me during that stressful situation. A few months later, he was there for me again when I needed surgery and ensured that I was well taken care of.

I entitled this post “Renaissance Man” because Steve is exactly that. After graduation, he was commissioned as an Infantry officer. He graduated from Ranger School and served in the 82nd Airborne Division. Later, he participated in a highly competitive program, was selected to attend medical school, and became an Army doctor. In December 1989, as a medical doctor, he parachuted into Panama with Army Rangers as part of Operation Just Cause. That action earned him a gold star on his Master Parachutist Badge—a rare award for an Army doctor. He went on to earn a reputation as one of the Army’s outstanding surgeons. He had combat tours in Iraq and Afghanistan and was one of the authors of a highly regarded treatise, entitled War Surgery in Afghanistan and Iraq: A Series of Cases, 2003-2007.

On this most recent trip, I learned that Steve has yet another talent of which I was unaware. The airplane in the picture is an experimental airplane that he built by himself while working full time as a civilian surgeon at William Beaumont Army Medical Center in El Paso. I was astounded when he described the process of assembling the plane, which he accomplished in only two years. Because the airplane is experimental, he must log forty hours before he can take passengers. He’s working toward that goal, and I look forward to the day when he flies to Georgetown, Texas, and gives me a ride.

Courage and Drive ’75!

Slowing the Pace to Discover What's Really Important

I just finished The Hideaway by Lauren Denton. Ms. Denton is a Southern author, born and raised in Mobile, Alabama. Hence, she knows the region that is the setting of The Hideaway. The protagonist, Sara Jenkins, grew up in Sweet Bay, Alabama, but left and made a career for herself in New Orleans. When her grandmother dies, she returns to Sweet Bay to take care of the estate. That’s when things get interesting. Ms. Denton creates a colorful cast of characters, chief of which is Sara’s grandmother, Mags, who reminded me of Ouiser Boudreaux, in Steel Magnolias. The story jumps back and forth between the present and the early 1960s in order to explain things that are only hinted at in the beginning of the story. Although I’m not a fan of that technique, Ms. Denton pulls it off well. The pieces of the puzzle begin to come together when Sara finds a box in the attic containing some of Mags’s cherished mementos. There are love interests—past and present—and threats from an unscrupulous land developer and challenges that keep things interesting. In the end Ms. Denton provides an uplifting story that just might cause the reader to reflect on what is really important in life.

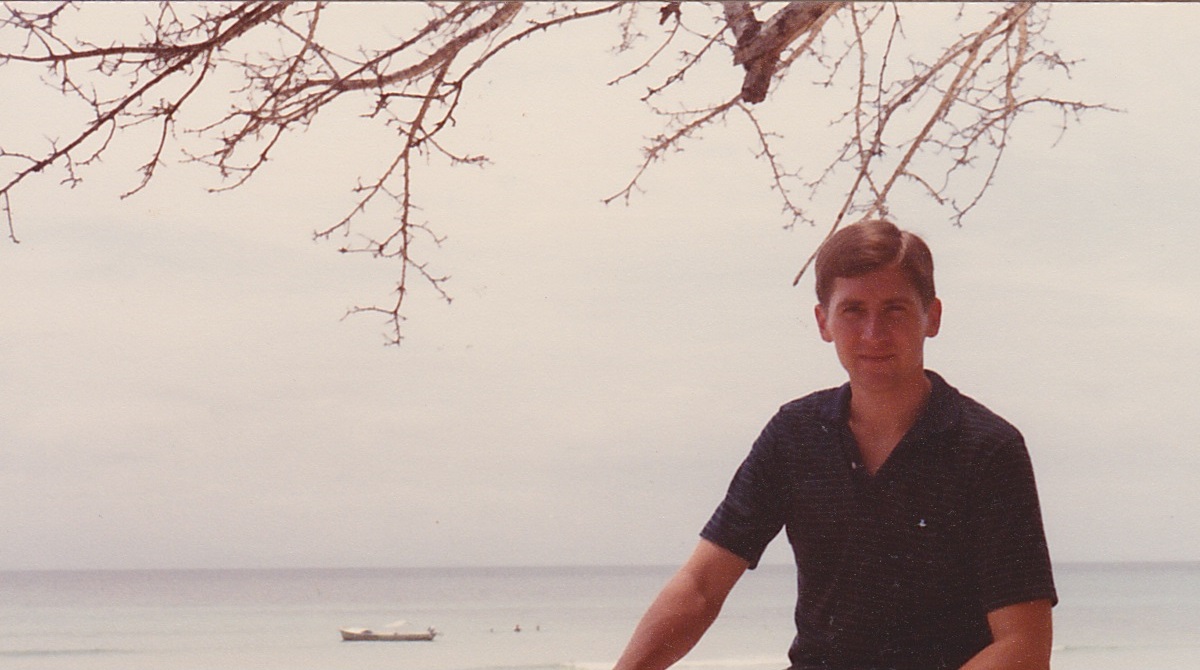

Reminiscing About Old Times

While cleaning out a closet, I came across some old photos from my time in Panama. (Click on the photo to advance the carousel.) It reminded me of what a wonderful experience it was, although I don’t remember looking like a kid. As I’ve mentioned before, Death in Panama is loosely based on my experiences in Panama in the early 1980s. There were some really good times, as evidenced by the smile on my face in some of these pictures, but there were also some gut-wrenching emotional times. The murder trial, on which much of Death in Panama is loosely based, was one of those times.

By the way, the protagonist in Death in Panama, Robert E. Clark, is a lot more handsome than yours truly.

An American Original: Andrew Jackson

I just finished reading Andrew Jackson: His Life and Times by H.W. Brands, a professor of history at the University of Texas at Austin. Brands is a talented writer who places the reader in the center of the exciting events surrounding one of our most colorful, yet controversial, presidents.

Jackson broke the mold. Though he was born in South Carolina, he was no Southern aristocrat. Orphaned at a young age, he literally fought his way to adulthood, culminating in his famous victory in the Battle of New Orleans at the end of the War of 1812. Jackson firmly believed in the right of the people to govern themselves, which constantly put him at odds with those—like John Quincy Adams—who believed ordinary Americans were unfit to govern themselves and could be dangerously swayed by demagogues. He guarded states’ rights against Federalists, because he believed state governments were more reliable in determining the will of the people. But more than anything Jackson believed in the Union and would vigorously oppose any perceived enemy—either foreign or domestic—that he believed threatened it.

The polarization of the country and its leaders during the middle of the 19th Century is described in vivid detail, evoking some disconcerting similarities with where we find ourselves today. Mr. Brands’s book is well worth reading.

Day One: Cross-Country Tour

It’s day one of our cross-country trip to promote Death in Panama. We’re playing tag with Irma, but the first planned stop is Atlanta. We have events planned in Charleston, South Carolina; New York City; Darien, Connecticut; and Chatham, Massachusetts. We might even have an event in Grand Rapids, Michigan. Keep your fingers crossed that this trip will get the Word out!

Tom T. Hall: a Generous Southern Gentleman

When I was a teenager, my wonderful brother-in-law, Jimmy Wilson, introduced me to a remarkable artist named Tom T. Hall. Jimmy loved all sorts of country music from Johnny Cash to Willie Nelson. But one Sunday he told me about a new artist that he'd recently learned about named Tom T. Hall. Jimmy was excited about a new song of his called "Old Dogs and Children and Watermelon Wine."

As we listened to several Tom T. Hall tapes, I concluded that there was something truly special about him. He was not only a good singer, he was a wonderful songwriter. Some of his songs were funny, like "Harper Valley PTA." Some pulled on your heart strings, like "I Love." And some were absolute poetry, like "Old Dogs and Children and Watermelon Wine."

Years later, when I was writing Death in Panama, I was struggling with a chapter in which the main character, Robert E. Clark, goes fishing with his boss. The two men start talking about women and waxing nostalgic about their mothers and how women today don't measure up. A line from "Old Dogs and Children and Watermelon Wine" came to me. An old man is talking to a young man about life and at one point tells him: "You know women think about theyselves when men folk ain't around."

The line was perfect for what I wanted to convey in the chapter, but I knew that quoting the lyrics of a song is tricky because they are protected by copyright law. So, I took a chance and wrote Mr. Hall a letter requesting permission to quote his song. A couple of weeks later I received a letter back from him not only giving me permission to quote his famous song, but also noting that, like me, he had served in the Army. I was very pleased and wrote him a note thanking him.

When I finally completed Death in Panama four years later, I decided to mail Mr. Hall a copy of the book. Again, a couple of weeks later I received a gracious letter from him, thanking me for the book and commenting on some things in the chapter. I was overwhelmed that a big star like Tom T. Hall not only allowed me to quote one of his most famous songs, but was so gracious about the whole thing.

In a time when virulent, hateful speech spews from the television almost daily, it is comforting to know that there are still generous gentlemen in the world--even big shots like Tom T. Hall.

Thanks again, Mr. Hall.

Tom T. Hall

A "Gaffe"? Really?

In reporting on Panamanian President Juan Carlos Varela's recent visit to the White House, the Washington Post mocked President Trump's comment that we (meaning the United States) did a good job building the Canal. The Post gushed, "Within minutes, Twitter had seized on what it deemed the latest Trump gaffe."

Trying to pass the responsibility for the "gaffe" label to those who commented on Twitter is specious. The Washington Post has an agenda: they will do whatever they can to try to make President Trump look bad. Whether you voted for Mr. Trump or not, whether you like him or not, he is our President. And he deserves to be treated fairly.

The fact is, this time President Trump is correct. We did build the Panama Canal. At the time of its completion, the Canal was an unprecedented engineering accomplishment. As David McCullough notes in The Path Between the Seas, "Apart from wars, it represented the largest, most costly single effort ever before mounted anywhere on earth." It was a monumental achievement, on a par--for its time--with landing a man on the moon. And it secured a place for the United States among the world powers.

Yes, as President Varela quipped, we built it "about 100 years ago." But that in itself is remarkable, considering the equipment available at that time. And indeed the locks are still working as originally designed. The only significant change to the Canal since it was completed in 1914 has been the addition of an additional set of locks to accommodate larger ships.

Did the United States make mistakes along the way? Of course, we did. Some of those mistakes are explained in my novel Death in Panama. But in the main the United States accomplished a great thing by building the Canal. It made the world a better place and improved the lives of Panamanians who benefit from being located in one of the most important commercial centers in the world.

Death of a Tyrant

Manuel Noriega, the former military dictator of Panama, died on May 29, 2017. He was 83.

One of the most unusual experiences I had during my time in Panama in the early 1980s was meeting Manuel Noriega. There was no conversation, mind you. It was an official event at the officers’ club on Fort Amador. I shook hands with him in a receiving line and attempted some small talk, although he did not appear to understand English, which was strange given his long-time connection with the U.S. In fact, many Panamanians—from maids and gardeners to elite members of upper-class society—spoke English very well. Noriega seemed ill at ease at the event, unlike the smiling man-of-the-people one sees in pictures of him.

It was as if he was fulfilling some responsibility that he really did not want to do. At the time, he was the chief of military intelligence, a post given to him by his former mentor, Omar Torrijos, after a 1968 military coup. Torrijos was the Panamanian leader with whom President Carter negotiated the Panama Canal Treaty, which transferred control of the Canal to Panama.

General Torrijos died in a plane crash shortly before I arrived in Panama in January 1982. Unbeknownst to those of us who were not in the military intelligence, Noriega was, at the time of that reception, in the process of consolidating his power. He became the de facto ruler of Panama in December of 1983.

What was known to almost everyone in the military was that Noriega worked with the CIA. The Reagan Administration was worried about the Sandinistas in El Salvador, and Noriega provided a conduit for weapons, military equipment, and cash that the U.S. wanted to get into the hands of friendly forces throughout Central and South America. But he was also a major cocaine trafficker. Nevertheless, the U.S. intelligence officials continued their relationship with him because he was useful for their covert military operations in Latin America.

Noriega ruled Panama with a heavy hand. He repressed the media, expanded the military, persecuted his political opponents, controlled the outcomes of elections by fraud, and became a rich drug trafficker. His relationship with the U.S. soured because of these activities and because he sold intelligence information to opponents of the U.S. In 1988 the U.S. indicted Noriega on drug trafficking charges in Miami, Florida. Then, in 1989, the U.S. invaded Panama, removed Noriega from power, and brought him to the United States, where he was tried on eight counts of drug trafficking, racketeering, and money laundering. He was sentenced to forty years in prison, which was later reduced to thirty years.

When he was released from U.S. prison in September 2007, Noriega was extradited to France where he was tried for murder and money laundering, found guilty, and sentenced to seven years in prison. In 2011 Noriega was extradited to Panama to serve a twenty-year prison term. In March of this year he was operated on to remove a brain tumor. He developed a brain hemorrhage after the surgery, which led to his death.

It was ignominious end for the man who had once brandished a machete during an anti-American tirade and declared to the crowd, “Not one step back!”

What Would Momma Say?

It’s as old as King David and as modern as Tiger Woods. It affects macho men like Arnold Schwarzenegger and wimps like Woody Allen. Offenders can be serious men of great responsibility like General David Petraeus, as well as silly little men like former Congressman Anthony Weiner. It’s infidelity, and it is rampant in our culture.

The characters in Death in Panama unfortunately reflect what I saw when I lived there. Maybe it was the hot weather and beautiful Panamanian women that made them forget how they’d been raised. Or maybe the heat simply made them a little crazy. In any event, it was not uncommon to see men—who had probably been faithful church-goers back home—casually disregard their marriage vows.

Today, infidelity is an epidemic everywhere. Panama is no worse than Atlanta or Dallas or Houston or, certainly, Washington, D.C. The Internet has made it easy to find willing accomplices—sometimes paid, sometimes not.

The nagging question for me is: Why? Why do men feel the need to forsake the women to whom they pledged their love?

Research suggests that the answer is not what you might think. That is, it’s not for sex.

In his best-selling book, The Truth About Cheating, marriage counselor M. Gary Neuman reports on his survey of cheating and non-cheating men. Forty-eight percent of the men he surveyed said that the primary reason they cheated was because of emotional dissatisfaction. Only eight percent said sexual dissatisfaction was the main factor. “Our culture tells us that all men need to be happy is sex, says Neuman. “But men are emotionally driven beings too. They want their wives to show them that they’re appreciated, and they want women to understand how hard they’re trying to get things right.”

So why do men feel unappreciated and misunderstood? Neuman concludes that the problem is cultural. “Most men consider it unmanly to ask for a pat on the back, which is why their emotional needs are often overlooked,” Neuman says.

His advice to women: “Create a marital culture of appreciation and thoughtfulness—and once you set the tone, he’s likely to match it.”

Relationships are complicated, and I don’t profess to have the answers. But I do think that it’s a problem that both men and women need to work on. Neuman found that the cheaters were not, as one might expect, uncaring cads. On the contrary, sixty-six percent of the cheaters said they felt guilt during the affair. And sixty-eight percent of them never dreamed they’d be unfaithful in the first place.

So, if guilt isn’t enough to stop men from cheating, what is?

Although it might sound like a throwback to the 1950s, Neuman suggests that women focus on their own behavior, because that’s something they completely control. He says they should show their appreciation, prioritize time together, and initiate sex more. In short, give your man man a reason to keep you at the front of his mind.

How Do We Know?

“The eye sees only what the mind is prepared to comprehend.”

Henri-Louis Bergson, French philosopher

In many respects, the characters in Death in Panama are no different from the rest of us. Sometimes, they sincerely believe something is true, when in fact it is not. Their error is not borne of malice; rather, it’s the result of misperception.

We can be fooled by the physical world. For example, we think that our eyes see color. In fact, what we perceive as color is actually the product of the surface properties of the object and how it reflects certain wavelengths of light. If the reflection of the light changes for some reason, such as different lighting conditions or haziness in the atmosphere, then the color of the object will change.

We can also be fooled because the perception of our senses can be distorted by our minds.

Let’s consider a few ways that can happen.

First, when we believe that something is true we tend to look for evidence that supports that belief and fail to notice evidence that tends to undermine it. Psychologists call this tendency the “confirmation bias” and have found that it is more pronounced in emotionally charged situations.

British psychologist Peter Wason conducted a series of experiments in the 1960s in which he asked participants to identify a rule that applies to a series of three numbers, such as 2-4-8. Participants were asked to construct other sets of three numbers to test their assumptions. Invariably, they tried sequences such as 16-32-64 or 3-6-12, all of which were correct. After a few tries, the subjects would stop, thinking they had discovered the rule. In fact, they had not. The rule was simply an increasing sequence of numbers. Almost all of the participants failed to discover the real rule, because they only tried numbers that confirmed their hypotheses. Very few tried to disprove their hypotheses.

Here's a quick video of the experiment:

To avoid the confirmation bias, we should check the evidence carefully before drawing a conclusion. We should be conscious of the tendency to see only evidence that supports a conclusion we’ve already drawn, and we should test our hypotheses by trying to disprove them. In short, each of us should keep an open mind.

Another distortion, related to the confirmation bias, is called the “anchoring effect.” The anchoring effect is the label psychologists give to a common human tendency to rely too heavily on the first piece of information that is offered; that is, the “anchor.” After the anchor is set, subsequent judgments are, to an extent, based on that first piece of information. That’s why car salesman like to set an initial price (the anchor), which then sets the standard for the remainder of the negotiations. After that, any price below the anchor seems more reasonable, even if it is still higher than what the car is really worth!

We should guard against the distortion caused by the anchoring effect by being cognizant of it. For example, if our first experience with someone is negative, we should not allow that experience to distort later interactions. They should be judged individually, as objectively as possible. If a salesman attempts to set a price—and make it an anchor—then we should get some comparisons. In fact, that is exactly what we’re doing when we comparison shop: we’re getting new price anchors.

Listen carefully to the instructions at the beginning of the video take the test:

After you take the test, scroll down to continue reading.

This experiment illustrates another distortion of perception, which occurs when we are focused intently on a certain thing. We can actually fail to see something that is right before our eyes. The failure to see is not based on the limits of our eyes, but on the limits of our minds. When our attention is focused intently on one thing, we fail to notice other, unexpected things.

As you can see from the test, we can miss important information that is right before us, if we are focused on something else. This distortion might cause us to miss information that would have led us to a different conclusion about a person or a situation.

Finally, our perception can be distorted because we simply don’t have all the facts. The person who cuts us off in traffic might be taking someone to the hospital. Or, he might be a jerk. Normally, we simply don’t have the whole story—the whole truth. Sometimes, we’re upset because we interpret situations or events—or give them assumed meanings—instead of focusing on what we can actually observe and confirm to be true. Sometimes our perceptions, and thus our reactions, are based on erroneous assumptions that would be different if we had more information.

Whether one is an investigator, like Jaime Hernandez, or a lawyer, like Robert E. Clark, or simply a human being trying to make his or her way in the world, it is extremely important to draw conclusions based on solid, objective evidence, not perceptions that can be distorted in ways we can’t even imagine.

The Faces of Poverty

Before I moved to Panama in 1982, I thought I knew what poverty was. I didn’t. As recounted in Death in Panama and in other blogs on this Web site, the sights, sounds, and smells of Panama’s poverty were heartbreaking. But I was only an observer from afar. I understood very little about poverty until much later.

By 1997, I had left active duty in the Army and moved my family to an Atlanta suburb. We went to a church where the parking lot was full of late-model cars, and the pews were full of freshly scrubbed and well-dressed worshippers. One Sunday, the pastor made an announcement about a “mission” trip to Honduras. As I was to learn later, the “mission” was one of assistance, not spreading the Gospel: the people we helped in Honduras were already well aware of God’s word. In fact, they knew it better than most of us who went on that mission trip.

That summer, a team of about fifteen men and women went to a small town near La Ceiba, Honduras, where we helped to rebuild a church that had been almost demolished by a storm. Every day, we labored in the searing sun, building pews and putting a new roof on the structure. We had to wear gloves when we worked on the roof, because the metal got too hot to touch. We worked side-by-side the members of the church, most of whom were taking time away from jobs, thereby reducing their already meager incomes. There was a language barrier, of course, but we worked through that with lots of smiles and what looked like a continuous game of Charades.

That trip to Honduras was followed by four mission trips to Peru. On the last two, I took my youngest daughter, who was fourteen years old during her first trip and fifteen on her last. We visited an orphanage in Lima and travelled by bus over a two-lane, winding road up the Andes Mountains—over 15,000 feet—and down the other side to a little town called San Ramon. Just as I had in Honduras, my daughter and I worked and worshipped with people who were struggling to survive.

One morning, a tiny, elderly lady appeared at the worksite with a pitcher of orange juice that was almost half her size—her gift to her friends from North America. She walked around and gave each of us a cupful. We later learned that she lived in a shack with a dirt floor. She had arisen before dawn and gone into the jungle to pick the oranges she used to make her gift. The fresh juice was unbelievably good—a far cry from the pale substitute we normally get from a frozen can. We concluded that it was more wonderful than any we’d ever had, because of the love that must have gone into it.

I learned some valuable lessons during those trips to Honduras and Peru. I learned that I’m extremely lucky to have been born where I was. I now understand—in ways that are unforgettable—that the opportunities all of us take for granted are unknown to most of the world. In addition, poverty is no longer an abstract concept for me. It has a human face—many human faces. My Bible bears inscriptions from Cinthya Bazán and Victor Ramirez and many other friends I will probably never see again. But they touched my heart in ways that are difficult to describe. They are people who—just like me—are trying to make their way in the world, although their paths are much tougher than mine.

Life has shown me that sometimes people are poor because they’ve made bad choices or simply had bad luck. Many other times—in places like Panama and Honduras and Peru—nothing they can do will change their circumstance. If they are born into poverty, there is little chance they will escape it. Nevertheless, they are human beings who love and laugh and hurt and cry. And, they hope that somehow tomorrow will be a better day.